Stig Östlund

fredag, januari 31, 2020

This simple trick will be your best shot at protecting yourself against the Wuhan virus There is no known cure for the China coronavirus, but this is one way to reduce the likelihood of infection

Everyone is freaking about the new virus that has come out of Wuhan, China, as

it seems doomed to rapidly spread across the world. While we don’t know

everything about it and there is no vaccine or known cure, there is one simple

thing you can do, to improve your chances of not getting it.

it seems doomed to rapidly spread across the world. While we don’t know

everything about it and there is no vaccine or known cure, there is one simple

thing you can do, to improve your chances of not getting it.

Wash your hands properly.

We don’t mean that you need to be obsessive about it, but possibly extra careful

to ensure that you wash your hands.

to ensure that you wash your hands.

You need to wash your hands:

● every time you go to the toilet

● before every meal

● every time you have been out in public

It’s not good enough to just twiddle your fingers under a dribble of water, flick

it off and think you’re done. Oh no.

it off and think you’re done. Oh no.

Here’s how to do it properly, and why each step is important.

- Wash your hands under a full stream of water if you can, so that the water

- flushes away the germs.

- Use soap. Water on its own does not break down the shells of germs like

- bacteria and viruses. Bleach and soap do.

- Take your time. We get it, you’re rushed. But don’t rush washing your

- hands. The germs are only broken down by actual manual rubbing for a

- certain amount of time. The general rule is you should wash your mitts

- for two verses of Happy Birthday.

- Don’t just wash your palms. Yes, your fingers and palms are most likely

- to have been touching things, but don’t leave out the back of your hands,

- and right up your arms to the far side of your watch strap. You can

- visualise this as the “glove” area of your hand.

- Rinse your hands while rubbing, making sure to get all of the soap off.

- Dry your hands. You can decide if you want to use paper or the hot air

- blowers

- or a facecloth you keep on you for this purpose, but don’t leave the

- bathroom with wet hands.

- If using a public bathroom, use a tissue to grasp the door handle on your way out

Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) from Wuhan is currently causing concern in the medical community as the virus is spreading around the world. Since its identification in late December 2019, the number of cases from China that have been imported into other countries is on the rise, and the epidemiologic picture is changing on a daily basis. We are reporting a case of 2019-nCoV infection acquired outside of Asia in which transmission appears to have occurred during the incubation period in the index patient.

A 33-year-old otherwise healthy German businessman (Patient 1) became ill with a sore throat, chills, and myalgias on January 24, 2020. The following day, a fever of 39.1°C (102.4°F) developed, along with a productive cough. By the evening of the next day, he started feeling better and went back to work on January 27.

Figure 1.(See below) Timeline of Exposure to Index Patient with Asymptomatic 2019-CoV Infection in Germany.

Timeline of Exposure to Index Patient with Asymptomatic 2019-CoV Infection in Germany.

Before the onset of symptoms, he had attended meetings with a Chinese business partner at his company near Munich on January 20 and 21. The business partner, a Shanghai resident, had visited Germany between Jan. 19 and 22. During her stay, she had been well with no signs or symptoms of infection but had become ill on her flight back to China, where she tested positive for 2019-nCoV on January 26 (index patient in Figure 1).

On January 27, she informed the company about her illness. Contact tracing was started, and the above-mentioned colleague was sent to the Division of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine in Munich for further assessment. At presentation, he was afebrile and well. He reported no previous or chronic illnesses and had no history of foreign travel within 14 days before the onset of symptoms. Two nasopharyngeal swabs and one sputum sample were obtained and were found to be positive for 2019-nCoV on quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (qRT-PCR) assay. Follow-up qRT-PCR assay revealed a high viral load of 108 copies per milliliter in his sputum during the following days, with the last available result on January 29.

On January 28, three additional employees at the company tested positive for 2019-nCoV (Patients 2 through 4 in Figure 1). Of these patients, only Patient 2 had contact with the index patient; the other two patients had contact only with Patient 1. In accordance with the health authorities, all the patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV infection were admitted to a Munich infectious diseases unit for clinical monitoring and isolation. So far, none of the four confirmed patients show signs of severe clinical illness.

This case of 2019-nCoV infection was diagnosed in Germany and transmitted outside of Asia. However, it is notable that the infection appears to have been transmitted during the incubation period of the index patient, in whom the illness was brief and nonspecific.

The fact that asymptomatic persons are potential sources of 2019-nCoV infection may warrant a reassessment of transmission dynamics of the current outbreak. In this context, the detection of 2019-nCoV and a high sputum viral load in a convalescent patient (Patient 1) arouse concern about prolonged shedding of 2019-nCoV after recovery. Yet, the viability of 2019-nCoV detected on qRT-PCR in this patient remains to be proved by means of viral culture.

Despite these concerns, all four patients who were seen in Munich have had mild cases and were hospitalized primarily for public health purposes. Since hospital capacities are limited — in particular, given the concurrent peak of the influenza season in the northern hemisphere — research is needed to determine whether such patients can be treated with appropriate guidance and oversight outside the hospital.

Camilla Rothe, M.D.

Mirjam Schunk, M.D.

Peter Sothmann, M.D.

Gisela Bretzel, M.D.

Guenter Froeschl, M.D.

Claudia Wallrauch, M.D.

Thorbjörn Zimmer, M.D.

Verena Thiel, M.D.

Christian Janke, M.D.

University Hospital LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

rothe@lrz.uni-muenchen.de

Mirjam Schunk, M.D.

Peter Sothmann, M.D.

Gisela Bretzel, M.D.

Guenter Froeschl, M.D.

Claudia Wallrauch, M.D.

Thorbjörn Zimmer, M.D.

Verena Thiel, M.D.

Christian Janke, M.D.

University Hospital LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

rothe@lrz.uni-muenchen.de

Wolfgang Guggemos, M.D.

Michael Seilmaier, M.D.

Klinikum München-Schwabing, Munich, Germany

Michael Seilmaier, M.D.

Klinikum München-Schwabing, Munich, Germany

Christian Drosten, M.D.

Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Patrick Vollmar, M.D.

Katrin Zwirglmaier, Ph.D.

Sabine Zange, M.D.

Roman Wölfel, M.D.

Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology, Munich, Germany

Katrin Zwirglmaier, Ph.D.

Sabine Zange, M.D.

Roman Wölfel, M.D.

Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology, Munich, Germany

Michael Hoelscher, M.D., Ph.D.

University Hospital LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

University Hospital LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

This letter was published on January 30, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Ur debattartikel i dagens DN:

WHO listade år 2018 de tio största infektionshoten mot mänskligheten, och nio av dem är virus (se faktaruta). Det finns varken läkemedel eller vaccin för någon av dessa infektioner. Vi menar att detta budskap inte tillräckligt har uppmärksammats vare sig av medier eller av beslutsfattare. Globalt spridda virus kan snabbt utvecklas till hot mot folkhälsan, vilket med all tydlighet aktualiseras av det nya coronaviruset (2019-nCoV) från Wuhan-regionen i Kina.

WHO listade år 2018 de tio största infektionshoten mot mänskligheten, och nio av dem är virus (se faktaruta). Det finns varken läkemedel eller vaccin för någon av dessa infektioner. Vi menar att detta budskap inte tillräckligt har uppmärksammats vare sig av medier eller av beslutsfattare. Globalt spridda virus kan snabbt utvecklas till hot mot folkhälsan, vilket med all tydlighet aktualiseras av det nya coronaviruset (2019-nCoV) från Wuhan-regionen i Kina.

Jan Albert, professor i smittskydd, särskilt klinisk virologi, Karolinska institutet

Niklas Arnberg, professor i virologi, Umeå universitet, ordförande, Svenska sällskapet för virologi

Mikael Berg, professor i veterinärmedicinsk virologi, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet

Tomas Bergström, seniorprofessor i klinisk mikrobiologi, Göteborgs universitet

Kristina Broliden, professor i infektionssjukdomar, Karolinska institutet

Magnus Evander, professor i virologi, Umeå universitet

Marianne Jansson, docent i virologi, Lunds universitet

Martin Lagging, professor i klinisk virologi, Göteborgs universitet

Magnus Lindh, professor i klinisk virologi, Göteborgs universitet

Mikael Lindberg, professor i virologi, Linnéuniversitetet

Åke Lundkvist, professor i virologi, Uppsala universitet

Ali Mirazimi, adjungerad professor i virologi, Karolinska institutet, Statens veterinärmedicinska anstalt.

Helene Norder, adjungerad professor i virologi, Göteborgs universitet

Kristina Nyström, docent i virologi, Göteborgs universitet.

Björn Olsen, professor i infektionssjukdomar, Uppsala universitet

Stefan Schwartz, professor i medicinsk mikrobiologi, Lunds universitet

Lennart Svensson, professor i molekylär virologi, Linköpings universitet, Karolinska institutet

Corona virus

The number of coronavirus cases worldwide has surpassed that of the Sars epidemic, which spread to more than two dozen countries in 2003.

There were around 8,100 cases of Sars - severe acute respiratory syndrome - reported during the eight-month outbreak.

But nearly 10,000 cases of the new virus have been confirmed, most in China, since it emerged in December.

Countries and territories that have confirmed cases: Thailand, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, Australia, Malaysia, Macau, Russia, France, the United States, South Korea, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, Canada, Britain, Vietnam, Italy, India, the Philippines, Nepal, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Finland and Sweden (= Jönköping).

"Det är viktigt att komma ihåg att enstaka fall inte är samma sak som att vi har en smittspridning i Sverige. Den risken bedömer vi för närvarande som mycket låg utifrån erfarenheter från andra länder", skriver Karin Tegmark Wisell, avdelningschef på Folkhälsomyndigheten, i ett pressmeddelande.

Här är japanska Kubotas autonoma el-traktor /Ny Teknik

Den japanska traktortillverkaren Kubota firar bolagets 130-årsjubileum genom att plocka bort människan ur ekvationen. Deras konceptfordon Kubota X Tractor navigerar med hjälp av artificiell intelligens och drivs av litiumjonbatterier kombinerat med solceller.

Robottraktorn är en del i den pågående utvecklingen där jordbruket är på väg mot fjärrstyrning och automation. Exempelvis startade forskningsinstitutet Rise en testbädd för digitaliserat jordbruk 2018 på Lantbruksuniversitetet Campus Ulltuna. Globalt har vad som kallas den fjärde jordbruksrevolutionen redan inletts, och den kan vara en nödvändighet. Med låg nativitet har Japans jordbruk svårt att rekrytera arbetare, och även i Sverige tillhör bönderna en åldrande yrkesgrupp.

State Department tells Americans not to travel to China.

The State Department on Thursday night issued a travel advisory telling Americans not to travel to China because of the public health threat posed by the coronavirus. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo confirmed the travel advisory on Twitter

The department set the new advisory at Level 4, or Red, its highest caution, which is reserved for the most dangerous situations.

Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

torsdag, januari 30, 2020

Internationella hälsonödlägen – det här hände då

Världshälsoorganisationen WHO har fem gånger tidigare utlyst internationellt hälsonödläge.

April 2009: H1N1, också känt som fågelinfluensa, började spridas från Mexiko och USA. Över 200 000 togs in för sjukhusvård och omkring 12 000 avled.

Mars 2014: Ebolavirus uppdagas i Guinea i Västafrika. Två och ett halvt år senare hade omkring 28 000 drabbats och 11 000 avlidit.

Maj 2014: Polio sprids i Afghanistan, Pakistan och Nigeria. Antalet diagnoser och dödsfall är oklart.

Februari 2016: Zikavirus sprids i huvudsak i Syd- och Nordamerika. Viruset, som bärs av bland annat myggor, visar sig ha rötterna i Brasilien. Antalet diagnoser och dödsfall är oklart.

Juli 2019: Ebolavirus bryter ut i Kongo-Kinshasa. Utbrottet pågår fortfarande, men antalet fall minskar ständigt. WHO:s nödkommitté anser att myndigheter fått kontroll på läget.

WHO skapade rutinerna för ett internationellt hälsonödläge 2005. Det skedde efter utbrotten av sars och fågelinfluensa i början av 2000-talet.

Källa: Deutsche Welle, THL, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

Cotonavirus. Here’s what you need to know: 16.10 Swedish Time

The W.H.O. will meet to decide if the epidemic is a global emergency.

- 170 people have died. More than 7,711 cases have been confirmed.

- China now has more cases of the virus than it had of SARS — but comparing the two is tricky.

- Wuhan residents lashed out over handling of the outbreak.

- In eerily quiet Wuhan, few people are venturing out except for food.

- Thousands of people are trapped aboard a cruise ship over possible infections.

- Russia orders partial closure of its border with China and limit visas.

Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia

Abstract

BACKGROUND

The initial cases of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–infected pneumonia (NCIP) occurred in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 and January 2020. We analyzed data on the first 425 confirmed cases in Wuhan to determine the epidemiologic characteristics of NCIP.

METHODS

We collected information on demographic characteristics, exposure history, and illness timelines of laboratory-confirmed cases of NCIP that had been reported by January 22, 2020. We described characteristics of the cases and estimated the key epidemiologic time-delay distributions. In the early period of exponential growth, we estimated the epidemic doubling time and the basic reproductive number.

RESULTS

Among the first 425 patients with confirmed NCIP, the median age was 59 years and 56% were male. The majority of cases (55%) with onset before January 1, 2020, were linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, as compared with 8.6% of the subsequent cases. The mean incubation period was 5.2 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.1 to 7.0), with the 95th percentile of the distribution at 12.5 days. In its early stages, the epidemic doubled in size every 7.4 days. With a mean serial interval of 7.5 days (95% CI, 5.3 to 19), the basic reproductive number was estimated to be 2.2 (95% CI, 1.4 to 3.9).

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of this information, there is evidence that human-to-human transmission has occurred among close contacts since the middle of December 2019. Considerable efforts to reduce transmission will be required to control outbreaks if similar dynamics apply elsewhere. Measures to prevent or reduce transmission should be implemented in populations at risk. (Funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and others.)

Since December 2019, an increasing number of cases of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–infected pneumonia (NCIP) have been identified in Wuhan, a large city of 11 million people in central China. On December 29, 2019, the first 4 cases reported, all linked to the Huanan (Southern China) Seafood Wholesale Market, were identified by local hospitals using a surveillance mechanism for “pneumonia of unknown etiology” that was established in the wake of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak with the aim of allowing timely identification of novel pathogens such as 2019-nCoV.In recent days, infections have been identified in other Chinese cities and in more than a dozen countries around the world.Here, we provide an analysis of data on the first 425 laboratory-confirmed cases in Wuhan to describe the epidemiologic characteristics and transmission dynamics of NCIP.

Since December 2019, an increasing number of cases of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–infected pneumonia (NCIP) have been identified in Wuhan, a large city of 11 million people in central China. On December 29, 2019, the first 4 cases reported, all linked to the Huanan (Southern China) Seafood Wholesale Market, were identified by local hospitals using a surveillance mechanism for “pneumonia of unknown etiology” that was established in the wake of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak with the aim of allowing timely identification of novel pathogens such as 2019-nCoV.In recent days, infections have been identified in other Chinese cities and in more than a dozen countries around the world.Here, we provide an analysis of data on the first 425 laboratory-confirmed cases in Wuhan to describe the epidemiologic characteristics and transmission dynamics of NCIP.

Methods

SOURCES OF DATA

The earliest cases were identified through the “pneumonia of unknown etiology” surveillance mechanism.Pneumonia of unknown etiology is defined as an illness without a causative pathogen identified that fulfills the following criteria: fever (≥38°C), radiographic evidence of pneumonia, low or normal white-cell count or low lymphocyte count, and no symptomatic improvement after antimicrobial treatment for 3 to 5 days following standard clinical guidelines. In response to the identification of pneumonia cases and in an effort to increase the sensitivity for early detection, we developed a tailored surveillance protocol to identify potential cases on January 3, 2020, using the case definitions described below.Once a suspected case was identified, the joint field epidemiology team comprising members from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) together with provincial, local municipal CDCs and prefecture CDCs would be informed to initiate detailed field investigations and collect respiratory specimens for centralized testing at the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, in Beijing. A joint team comprising staff from China CDC and local CDCs conducted detailed field investigations for all suspected and confirmed 2019-nCoV cases.

Data were collected onto standardized forms through interviews of infected persons, relatives, close contacts, and health care workers. We collected information on the dates of illness onset, visits to clinical facilities, hospitalization, and clinical outcomes. Epidemiologic data were collected through interviews and field reports. Investigators interviewed each patient with infection and their relatives, where necessary, to determine exposure histories during the 2 weeks before the illness onset, including the dates, times, frequency, and patterns of exposures to any wild animals, especially those purportedly available in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, or exposures to any relevant environments such as that specific market or other wet markets. Information about contact with others with similar symptoms was also included. All epidemiologic information collected during field investigations, including exposure history, timelines of events, and close contact identification, was cross-checked with information from multiple sources. Households and places known to have been visited by the patients in the 2 weeks before the onset of illness were also investigated to assess for possible animal and environmental exposures. Data were entered into a central database, in duplicate, and were verified with EpiData software (EpiData Association).

CASE DEFINITIONS

The initial working case definitions for suspected NCIP were based on the SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) case definitions, as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2003 and 2012A suspected NCIP case was defined as a pneumonia that either fulfilled all the following four criteria — fever, with or without recorded temperature; radiographic evidence of pneumonia; low or normal white-cell count or low lymphocyte count; and no reduction in symptoms after antimicrobial treatment for 3 days, following standard clinical guidelines — or fulfilled the abovementioned first three criteria and had an epidemiologic link to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market or contact with other patients with similar symptoms. The epidemiologic criteria to define a suspected case were updated on January 18, 2020, once new information on identified cases became available. The criteria were the following: a travel history to Wuhan or direct contact with patients from Wuhan who had fever or respiratory symptoms, within 14 days before illness onset.A confirmed case was defined as a case with respiratory specimens that tested positive for the 2019-nCoV by at least one of the following three methods: isolation of 2019-nCoV or at least two positive results by real-time reverse-transcription–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay for 2019-nCoV or a genetic sequence that matches 2019-nCoV.

LABORATORY TESTING

The 2019-nCoV laboratory test assays were based on the previous WHO recommendation.Upper and lower respiratory tract specimens were obtained from patients. RNA was extracted and tested by real-time RT-PCR with 2019-nCoV–specific primers and probes. Tests were carried out in biosafety level 2 facilities at the Hubei (provincial) CDC and then at the National Institute for Viral Disease Control at China CDC. If two targets (open reading frame 1a or 1b, nucleocapsid protein) tested positive by specific real-time RT-PCR, the case would be considered to be laboratory-confirmed. A cycle threshold value (Ct-value) less than 37 was defined as a positive test, and a Ct-value of 40 or more was defined as a negative test. A medium load, defined as a Ct-value of 37 to less than 40, required confirmation by retesting. If the repeated Ct-value was less than 40 and an obvious peak was observed, or if the repeated Ct-value was less than 37, the retest was deemed positive. The genome was identified in samples of bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid from the patient by one of three methods: Sanger sequencing, Illumina sequencing, or nanopore sequencing. Respiratory specimens were inoculated in cells for viral isolation in enhanced biosafety laboratory 3 facilities at the China CDC.3

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The epidemic curve was constructed by date of illness onset, and key dates relating to epidemic identification and control measures were overlaid to aid interpretation. Case characteristics were described, including demographic characteristics, exposures, and health care worker status. The incubation period distribution (i.e., the time delay from infection to illness onset) was estimated by fitting a log-normal distribution to data on exposure histories and onset dates in a subset of cases with detailed information available. Onset-to-first-medical-visit and onset-to-admission distributions were estimated by fitting a Weibull distribution on the dates of illness onset, first medical visit, and hospital admission in a subset of cases with detailed information available. We fitted a gamma distribution to data from cluster investigations to estimate the serial interval distribution, defined as the delay between illness onset dates in successive cases in chains of transmission.

We estimated the epidemic growth rate by analyzing data on the cases with illness onset between December 10 and January 4, because we expected the proportion of infections identified would increase soon after the formal announcement of the outbreak in Wuhan on December 13. We fitted a transmission model (formulated with the use of renewal equations) with zoonotic infections to onset dates that were not linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, and we used this model to derive the epidemic growth rate, the epidemic doubling time, and the basic reproductive number (R0), which is defined as the expected number of additional cases that one case will generate, on average, over the course of its infectious period in an otherwise uninfected population. We used an informative prior distribution for the serial interval based on the serial interval of SARS with a mean of 8.4 and a standard deviation of 3.8.

Analyses of the incubation period, serial interval, growth rate, and R0 were performed with the use of MATLAB software (MathWorks). Other analyses were performed with the use of SAS software (SAS Institute) and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

ETHICS APPROVAL

Data collection and analysis of cases and close contacts were determined by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China to be part of a continuing public health outbreak investigation and were thus considered exempt from institutional review board approval.

Results

Results

Figure 1. (See below) Onset of Illness among the First 425 Confirmed Cases of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–Infected Pneumonia (NCIP) in Wuhan, China.The development of the epidemic follows an exponential growth in cases, and a decline in the most recent days is likely to be due to under-ascertainment of cases with recent onset and delayed identification and reporting rather than a true turning point in incidence (Figure 1). Specifically, the latter part of the curve does not indicate a decrease in the number of incident cases but is due to delayed case ascertainment at the cutoff date. Care should be taken in interpreting the speed of growth in cases in January, given an increase in the availability and use of testing kits as time has progressed. The majority of the earliest cases included reported exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, but there was an exponential increase in the number of nonlinked cases beginning in late December.

Onset of Illness among the First 425 Confirmed Cases of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–Infected Pneumonia (NCIP) in Wuhan, China.The development of the epidemic follows an exponential growth in cases, and a decline in the most recent days is likely to be due to under-ascertainment of cases with recent onset and delayed identification and reporting rather than a true turning point in incidence (Figure 1). Specifically, the latter part of the curve does not indicate a decrease in the number of incident cases but is due to delayed case ascertainment at the cutoff date. Care should be taken in interpreting the speed of growth in cases in January, given an increase in the availability and use of testing kits as time has progressed. The majority of the earliest cases included reported exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, but there was an exponential increase in the number of nonlinked cases beginning in late December.

Table (See below): Characteristics of Patients with Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan as of January 22, 2020.

Characteristics of Patients with Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan as of January 22, 2020.

Key Time-to-Event Distributions.Figure 3 (See below)

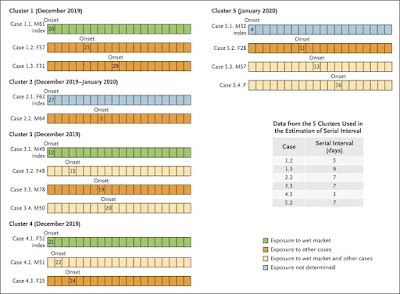

Key Time-to-Event Distributions.Figure 3 (See below) Detailed Information on Exposures and Dates of Illness Onset in Five Clusters Including 16 Cases.

Detailed Information on Exposures and Dates of Illness Onset in Five Clusters Including 16 Cases.

Onset of Illness among the First 425 Confirmed Cases of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–Infected Pneumonia (NCIP) in Wuhan, China.The development of the epidemic follows an exponential growth in cases, and a decline in the most recent days is likely to be due to under-ascertainment of cases with recent onset and delayed identification and reporting rather than a true turning point in incidence (Figure 1). Specifically, the latter part of the curve does not indicate a decrease in the number of incident cases but is due to delayed case ascertainment at the cutoff date. Care should be taken in interpreting the speed of growth in cases in January, given an increase in the availability and use of testing kits as time has progressed. The majority of the earliest cases included reported exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, but there was an exponential increase in the number of nonlinked cases beginning in late December.

Onset of Illness among the First 425 Confirmed Cases of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–Infected Pneumonia (NCIP) in Wuhan, China.The development of the epidemic follows an exponential growth in cases, and a decline in the most recent days is likely to be due to under-ascertainment of cases with recent onset and delayed identification and reporting rather than a true turning point in incidence (Figure 1). Specifically, the latter part of the curve does not indicate a decrease in the number of incident cases but is due to delayed case ascertainment at the cutoff date. Care should be taken in interpreting the speed of growth in cases in January, given an increase in the availability and use of testing kits as time has progressed. The majority of the earliest cases included reported exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, but there was an exponential increase in the number of nonlinked cases beginning in late December.Table (See below):

Characteristics of Patients with Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan as of January 22, 2020.

Characteristics of Patients with Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan as of January 22, 2020.

The median age of the patients was 59 years (range, 15 to 89), and 240 of the 425 patients (56%) were male. There were no cases in children below 15 years of age. We examined characteristics of cases in three time periods: the first period was for patients with illness onset before January 1, which was the date the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was closed; the second period was for those with onset between January 1 and January 11, which was the date when RT-PCR reagents were provided to Wuhan; and the third period was those with illness onset on or after January 12 (Table 1). The patients with earlier onset were slightly younger, more likely to be male, and much more likely to report exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. The proportion of cases in health care workers gradually increased across the three periods (Table 1).

Figure 2 (See below:) Key Time-to-Event Distributions.Figure 3 (See below)

Key Time-to-Event Distributions.Figure 3 (See below) Detailed Information on Exposures and Dates of Illness Onset in Five Clusters Including 16 Cases.

Detailed Information on Exposures and Dates of Illness Onset in Five Clusters Including 16 Cases.

We examined data on exposures among 10 confirmed cases, and we estimated the mean incubation period to be 5.2 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.1 to 7.0); the 95th percentile of the distribution was 12.5 days (95% CI, 9.2 to 18) (Figure 2A). We obtained information on 5 clusters of cases, shown in Figure 3. On the basis of the dates of illness onset of 6 pairs of cases in these clusters, we estimated that the serial interval distribution had a mean (±SD) of 7.5±3.4 days (95% CI, 5.3 to 19) (Figure 2B).

In the epidemic curve up to January 4, 2020, the epidemic growth rate was 0.10 per day (95% CI, 0.050 to 0.16) and the doubling time was 7.4 days (95% CI, 4.2 to 14). Using the serial interval distribution above, we estimated that R0 was 2.2 (95% CI, 1.4 to 3.9).

The duration from illness onset to first medical visit for 45 patients with illness onset before January 1 was estimated to have a mean of 5.8 days (95% CI, 4.3 to 7.5), which was similar to that for 207 patients with illness onset between January 1 and January 11, with a mean of 4.6 days (95% CI, 4.1 to 5.1) (Figure 2C). The mean duration from onset to hospital admission was estimated to be 12.5 days (95% CI, 10.3 to 14.8) among 44 cases with illness onset before January 1, which was longer than that among 189 patients with illness onset between January 1 and 11 (mean, 9.1 days; 95% CI, 8.6 to 9.7) (Figure 2D). We did not plot these distributions for patients with onset on or after January 12, because those with recent onset and longer durations to presentation would not yet have been detected.

Discussion

Here we provide an initial assessment of the transmission dynamics and epidemiologic characteristics of NCIP. Although the majority of the earliest cases were linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market and the patients could have been infected through zoonotic or environmental exposures, it is now clear that human-to-human transmission has been occurring and that the epidemic has been gradually growing in recent weeks. Our findings provide important parameters for further analyses, including evaluations of the impact of control measures and predictions of the future spread of infection.

We estimated an R0 of approximately 2.2, meaning that on average each patient has been spreading infection to 2.2 other people. In general, an epidemic will increase as long as R0 is greater than 1, and control measures aim to reduce the reproductive number to less than 1. The R0 of SARS was estimated to be around 3, and SARS outbreaks were successfully controlled by isolation of patients and careful infection control. In the case of NCIP, challenges to control include the apparent presence of many mild infections and limited resources for isolation of cases and quarantine of their close contacts. Our estimate of R0 was limited to the period up to January 4 because increases in awareness of the outbreak and greater availability and use of tests in more recent weeks will have increased the proportions of infections ascertained. It is possible that subsequent control measures in Wuhan, and more recently elsewhere in the country as well as overseas, have reduced transmissibility, but the detection of an increasing number of cases in other domestic locations and around the world suggest that the epidemic has continued to increase in size. Although the population quarantine of Wuhan and neighboring cities since January 23 should reduce the exportation of cases to the rest of the country and overseas, it is now a priority to determine whether local transmission at a similar intensity is occurring in other locations.

It is notable that few of the early cases occurred in children, and almost half the 425 cases were in adults 60 years of age or older, although our case definition specified severe enough illness to require medical attention, which may vary according to the presence of coexisting conditions. Furthermore, children might be less likely to become infected or, if infected, may show milder symptoms, and either of these situations would account for underrepresentation in the confirmed case count. Serosurveys after the first wave of the epidemic would clarify this question. Although infections in health care workers have been detected, the proportion has not been as high as during the SARS and MERS outbreaks.One of the features of SARS and MERS outbreaks is heterogeneity in transmissibility, and in particular the occurrence of super-spreading events, particularly in hospitals. Super-spreading events have not yet been identified for NCIP, but they could become a feature as the epidemic progresses.

Although delays between the onset of illness and seeking medical attention were generally short, with 27% of patients seeking attention within 2 days after onset, delays to hospitalization were much longer, with 89% of patients not being hospitalized until at least day 5 of illness Figure2). This indicates the difficulty in identifying and isolating cases at an earlier stage of disease. It may be necessary to commit considerable resources to testing in outpatient clinics and emergency departments for proactive case finding, both as part of the containment strategy in locations without local spread yet as well as to permit earlier clinical management of cases. Such an approach would also provide important information on the subclinical infections for a better assessment of severity.

Our preliminary estimate of the incubation period distribution provides important evidence to support a 14-day medical observation period or quarantine for exposed persons. Our estimate was based on information from 10 cases and is somewhat imprecise; it would be important for further studies to provide more information on this distribution. When more data become available on epidemiologic characteristics of NCIP, a detailed comparison with the corresponding characteristics of SARS and MERS, as well as the four coronaviruses endemic in humans, would be informative.

Our study suffers from the usual limitations of initial investigations of infections with an emerging novel pathogen, particularly during the earliest phase, when little is known about any aspect of the outbreak and there is a lack of diagnostic reagents. To increase the sensitivity for early detection and diagnosis, epidemiology history was considered in the case identification and has been continually modified once more information has become available. Confirmed cases could more easily be identified after the PCR diagnostic reagents were made available to Wuhan on January 11, which helped us shorten the time for case confirmation. Furthermore, the initial focus of case detection was on patients with pneumonia, but we now understand that some patients can present with gastrointestinal symptoms, and an asymptomatic infection in a child has also been reportedEarly infections with atypical presentations may have been missed, and it is likely that infections of mild clinical severity have been under-ascertained among the confirmed cases. We did not have detailed information on disease severity for inclusion in this analysis.

In conclusion, we found that cases of NCIP have been doubling in size approximately every 7.4 days in Wuhan at this stage. Human-to-human transmission among close contacts has occurred since the middle of December and spread out gradually within a month after that. Urgent next steps include identifying the most effective control measures to reduce transmission in the community. The working case definitions may need to be refined as more is learned about the epidemiologic characteristics and outbreak dynamics. The characteristics of cases should continue to be monitored to identify any changes in epidemiology — for example, increases in infections among persons in younger age groups or health care workers. Future studies could include forecasts of the epidemic dynamics and special studies of person-to-person transmission in households or other locations, and serosurveys to determine the incidence of the subclinical infections would be valuable.These initial inferences have been made on a “line list” that includes detailed individual information on each confirmed case, but there may soon be too many cases to sustain this approach to surveillance, and other approaches may be required.

Supported by theMinistry of Science and Technology of China, the National Science and Technology Major Projects of China (2018ZX10201-002-008-002, 2018ZX10101002-003), the China–U.S. Collaborative Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Disease, and National Mega-Projects for Infectious Disease (2018ZX10201002-008-002), the National Natural Science Foundation (71934002), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease s (Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance [CEIRS] contract number HHSN272201400006C), and the Health and Medical Research Fun d (Hong Kong). None of the funders had any role in the study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication. The researchers confirm their independence from funders and sponsors.

Supported by the

Drs. Q. Li, X. Guan, P. Wu, and X. Wang and Drs. B. Cowling, B. Yang, M. Leung, and Z. Feng contributed equally to this article.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the China CDC. All the authors have declared no relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced this work.

This article was published on January 29, 2020, and updated on January 29, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Bloggarkiv

-

▼

2020

(2745)

-

▼

januari

(266)

- Berra filosoferar

- This simple trick will be your best shot at protec...

- Wuhan

- Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asympt...

- Ur debattartikel i dagens DN: WHO listade år 2018...

- Corona virus

- Här är japanska Kubotas autonoma el-traktor /Ny Te...

- Corona virus. 213 people have died. About 9,800 ca...

- State Department tells Americans not to travel to ...

- Statement on the second meeting of the Internation...

- World Health Organizatio...

- Trump impeachment: Republicans speak as trial ente...

- Berra filosoferar

- Internationella hälsonödlägen – det här hände då

- Jörn Donner

- Cotonavirus. Here’s what you need to know: 16.10 S...

- Wow

- Världens genom tiderna bäste tenorsaxofonist (Lest...

- Live

- Salsa

- Ingen rubrik

- Ingen rubrik

- Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of No...

- A Novel Coronavirus Emerging in China — Key Questi...

- Ingen rubrik

- Antalet döda i coronavirus-epidemin i Kina har nu ...

- These Images Show the Sun’s Surface in Greater Det...

- Is the World Ready for the Coronavirus?

- Halv miljon väljare har övergett S senaste året

- Avd. "Kungar pippar svart"

- Scientists are working to develop a vaccine capabl...

- The president of the United States - The Pacifier

- Trump Releases Mideast Peace Plan That Strongly Fa...

- Nu kan Coronavirusets spridning följas på nätet Vi...

- Ingen rubrik

- Ingen rubrik

- Impeachment Trial Day 7. Live

- When will there be a coronavirus vaccine? 5 questi...

- Dansk misstänks vara smittad av cornoavirus

- Corona virus

- Frequently clean hands by using alcohol-based hand...

- 33-årig tysk man smittad utan att ha besökt Kina

- Coronavirus Live Updates: More Than 4,000 Infected...

- Dagens pang-pang i The New Sweden

- Ingen rubrik

- Live

- Analys: Corunairuset är ett stort hot mot resebran...

- The turning point in the Nazis’ plan to “solve the...

- Aurora

- Världens största tvåmotoriga jetflygplan.

- "2019-nCoV"

- Coronavirus

- Kobe Bryant

- Efter coronalarmet – munskydd slut på apotek i Sve...

- Ingen rubrik

- Grammys 2020

- In Coronavirus, a ‘Battle’ That Could Humble China...

- Dagens pang-pang i The New Sweden

- Coronavirus Infections Expanding at a Growing Rate

- Ingen rubrik

- Corona virus

- Ingen rubrik

- WHO advice for international travel and trade in r...

- Corona virus

- Over 1,970 coronavirus cases confirmed in Chi...

- Coronavirus Live Updates: Death Toll Reaches 56, a...

- Dagens explosion i The New Sweden

- Ingen rubrik

- Muhammad Ali

- Record-breaking journey to the bottom of the ocean...

- Vad skulle hända om vi sprängde kärnvapen i Marian...

- NY STATISTIK: Sverige tar emot flest asyluzbeker -...

- The El Mozote Massacre (El Salvador)

- As of Jan. 24, there are more than 830 confirmed c...

- RIGHT NOW (NYT 08.30 Swedish time) A study in The ...

- Coronavirus: trois premiers cas confirmés en France

- Toll From Outbreak Climbs in China as Infections R...

- Onlineuppslagsverket Wikipedia passerade under tor...

- I dag gryr dagen i Stockholm 07:27. Solen går u...

- Many in China Wear Them, but Do Masks Block Corona...

- Trump impeachment trial - Live

- Corona virus

- Monty Python-stjärnan Terry Jones död – blev 77 år

- Ingen rubrik

- Dagens "Explosionernas och skjutandes New Sweden"

- Coronavirus

- Ingen rubrik

- Ingen rubrik

- Ingen rubrik

- Sossarna kan dra åt ......

- Mezzo

- Att tre av fyra personer som har stått och balanse...

- God svensk sjukvård försämras rejält på sina håll ...

- Dagens explosion i The New Sweden

- The Test a Deadly Coronavirus Outbreak Poses to Ch...

- Fransk polis använde tårgas och arresterade ett st...

- Bör kallas katastrof

- Sverigedemokraterna är med 24 procent nu för först...

- How Much Warmer Was Your City in 2019?

-

▼

januari

(266)